TY was born under the sound of the Bow Bells, London to Afrose and Olive. He was proud to be a cockney. He was as much an East End lad as he was the son of an Indo Guyanese muslim and a Lancashire lass. TY, with soft brown eyes and rich brown skin, hirsute, tattooed and pierced, he made a striking figure and was the youngest of five brothers. Working class, he began training as a nurse in his 20s. During a bout of depression he began to see himself hanging from the lamp posts outside Whipps Cross Hospital where he was based. Distressed and without any source of mental health support, he dropped out of the course. Naturally patient and compassionate he soon adapted his caring aptitude and transferred his skills to being a social care worker and worked with the elderly in care.

Nestled between Venezuela and Suriname, the former British colony of Guyana celebrates Indian Arrival Day on May 5 each year, commemorating the first arrival of indentured labourers from India to the country, on 5th May 1838. Guyana, culturally and socially part of the Caribbean, is the only English-speaking country in South America and gained its independence from the UK in 1966. In Guyana current reports of Covid total 31,359 cases.

Thoughtful, complex, handsome, vulnerable and tenacious, TY would struggle at school. He left school feeling frustrated, worthless and a failure. He remembers career advisors crudely trying to manage his expectations. They encouraged him to think small. He was crippled with self doubt, lack of self esteem and frustration. He found solace in death metal and spoke of an alcohol and drug fuelled twenties, using almost anything to numb the days. One day a week was put aside to go down to Oxford St to buy clobber – clothes – for the weekend’s clubbing. Something led him to the ‘rooms’ and the AA along with his inner resourcefulness offered him a level of self care and sobriety. If you met TY in a pub he would always order a half pint of pineapple juice.

TY had ADHD and dyslexia that was only diagnosed in adulthood. TY felt it held him back and exacted something from him. Hobbled social graces and made him feel like a misfit a dozen times over. He was unfortunate. He was one of the lost generation of neurodiverse people who were not given the learning support he deserved as a child. Despite this TY returned to education as a mature student and was very interested in and engaged with Queer cultures and Black and brown cultural production. He read and researched widely and was proud of his hard won achievements. For a long time his email signature, would be:

TY

BA Comparative Literature

MA Cultural Studies

PhD Candidate

Samuel Dixon Selvon fan

& Youngest son of Afrose & Olive

TY’s Indo-Guyanese father is in his 80s and is the descendant of what is politely referred to as indentured labourers but was in fact closer to a form of slavery. The emancipation of African slaves in British Guyana created a shortage of free Black and brown labour at the sugar plantations. To remedy that the ‘Gladstone Experiment’, the British state backed plan to exchange African bodies with more ‘pliant and servile’ Indian bodies was put into action. Indentured labourers were brought from India, men and women who were frequently kidnapped or hoodwinked into servitude. On May 5th 1838, 396 Indians, referred to as the ‘Gladstone Coolies’ arrived in Guyana. This was an extension of an oppressive, exploitative, inhuman system which was to continue for over three-quarters of a century. It is not unusual to learn that men of TY’s father’s age endured depths of poverty, neglect and inhumane treatment in their youth. Belonging to families who were too poor to move off the plantations where their antecedents had been indentured, they often found themselves beholden to the plantation master and his men. Young brown and Black boys were commonly used as unpaid labour, their spirits and self esteem crushed. Their days featured daily humiliations and violence. As men they dealt with these experiences with alcohol and gender based violence and failing psycho-emotional health. A legacy of trauma that TY’s Dad instinctively worked hard to try and escape and ended up working several jobs back to back in London, including being a hospital porter for the NHS. He was an incessant smoker with a cheeky smile, loved a good glass of whiskey and is still irresistible to the ladies.

Tota C. Manga writing for the Guyana Chronicle references the late Guyanese historian, Dr. Walter Rodney, as highlighting the harshness of the indentureship system and its “neo-slave nature”. However it must be stressed that indenture and slavery are not the same but in some senses two chapters in the history of colonialism. But trauma is trauma. Perhaps it may be reasonable to assume that Guyanese Indo-Caribbeans experienced an inherited, inter-generational trauma. They share an epigenetic experience of trauma. Recent research in the study of epigenetics delivers an unquestionable case that inherited trauma shapes your health, life outcomes and lived experience.

Who saw him die?

On July 19th 2021 the UK government declared Freedom day, the sitting opposition did little to assert their dissent. As of September 22nd 2021 there are over 4.5 million world-wide Covid reported deaths, of that figure, 135,000 deaths were in the UK. Black and brown people make up a significant proportion of that figure.

TY died on September 3rd 2021 at 5.13pm in an intensive care unit in the East End of London. His cause of death will be noted as complications due to Covid. For several years before and during the pandemic he worked as a key frontline night shift worker for an international delivery company. Like all frontline workers he couldn’t ‘dial in’ his labour – he was literally risking death travelling on public transport to get to his minimum wage job. Where would this bright and beautiful lonely Londoner be if he had had the understanding we now afford dyslexics and the neurodiverse? Where would his open and enquiring mind and spirit have taken him?

Reuters reported that “Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s ‘freedom day’ ending over a year of Covid lockdown restrictions in England was marred on Monday by surging infections, warnings of supermarket shortages and his own forced self-isolation… Johnson’s big day was marred by “pingdemic chaos” as a National Health Service app ordered hundreds of thousands of people to self-isolate – prompting warnings supermarket shelves could soon be emptied.”

TY lived in London and I lived in Scotland but we were very close and met as often as we could. We were friends and we loved one another and showed our intimate self’s to one another. TY was usually the first person to text me in the morning and the last to speak with me at night. We would share our day. Share our thoughts. Share our creative ideas. Share our moods. Share our highs and lows.

Who caught his blood?

Early in 2021 TY was diagnosed with Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and was undertaking chemotherapy. He had been reassured by his GP that if he was going to have cancer, this was the ‘right’ one to get. He was certain he would recover fully. On the morning of July 22nd 2021, 9 days before TY’s confirmed Covid diagnosis, I messaged and asked him how he was. He texts back that he is feeling unusually exhausted. I, having recently become an evangelical kefir drinker, urge him to drink probiotics. I sent him a link to one that also features claims to support the immune system against Covid. He says he would try it after he had finished chemo.

In Guyana the dead are usually washed and dressed by the family, not passed on as a task for the funeral home.There is a reason why in the UK we refer to a funeral ‘director’– the whole business of death here is a performance and a masterclass in control and reserve. A polite moment of grief and a quick goodbye. And yet funerals are for the living. In Guyana, like the rest of the Caribbean there is a gathering similar to a wake for mourning and saying farewell and then, nine days after the wake, there is a “nine night,” which is held in memory of the deceased. Nine nights are where family and friends gather and remember and share memories of the one who has passed. Muslim Guyanese, in accordance to Islamic tradition, must be buried and as soon as possible after death.

TY, like his father, had worked all his life and had never had a job that earned him more than the minimum wage. By July 24th 2021 he had taken temporary sick leave from his night shift job whilst he undertook chemotherapy. TY was passionate about storytelling, loved cinema and had applied for a film making course. He wasn’t accepted but the person who interviewed him, recognised his love of stories and narrative and urged TY to apply for the scriptwriting course. It was expensive and he didn’t have cash to spare, but TY was excited at the possibility of finding a voice and medium through which to share his lived experiences. His first course deadline was looming, TY felt his ADHD was stalling him and he felt panicked. I tried to boost his morale and encourage him. He did his best but lacked the energy to complete the script. At the time TY chalked it up to his ADHD but now I wonder if it wasn’t the beginnings of Covid and if he was in fact experiencing brain fog. I thought he was facing a familiar lack of self belief. When it became clear that TY wouldn’t meet the deadline I supported him to finally contact his tutor and ask for an extension. Not knowing that in 41 days TY would be dead.

Who will make his shroud?

A Guyanese flag was placed inside his coffin and TY was cremated at 1.15pm on September 24th 2021, 21 days after his unnecessary, entirely preventable death, in an East End crematorium far from the shadow of the Bow Bells. There was a swift half hour service where a white, female celebrant who never knew TY spoke about his life. Pantera by Black Sabbath was played to remember him. TY had eclectic tastes but he was very particular about his music. He was passionate about System of a Down, Sepultura and Soulfly and despite the fact I was far from a metalhead, would share with me Serj Takian and Max Cavalera anecdotes and music videos. TY was not a nationalist and although not religious, he did have a sense of spirituality and was interested in his muslim heritage. In anticipation of his elderly father’s death, TY had been researching muslim death rites. He had told me that he wanted a muslim funeral. He lit incense and kept an ofrenda style altar where he lit candles for people he wanted to send positive energies to. He told me he held a candle for me. In the years we were in each other’s lives, I never, ever heard TY play Black Sabbath. This funeral service followed by a brief gathering at a suburban golf club where sandwiches were served and people were encouraged to buy their own alcoholic drinks.

A little known fact is that there were Indians and Indo Caribbeans who arrived on the historic passenger liner, the Empire Windrush. Their experiences have been largely overlooked. Precisely 138 years later Nicolas Bosten notes in the Independent newspaper that “When (Indo-Caribbean) Lynda Mahabir won her immigration case in court(…)it was a victory for all Windrush campaigners. However, it also drew attention to a less visible group, the Indo-Caribbean members of the Windrush generation. The UK census has no classification for “Indo-Caribbean” as it does “Black Caribbean”, therefore exact numbers are unavailable. The closest census designation is “Asian Other”, which counted 835,720 people.”

Who will dig his grave?

TY had had asthma from boyhood. He remembers the tightness in his chest when his brothers would jump on him as a child. Rough play between brothers, later would become a familiar scapegoating. The hands over his mouth and nose as he was brought down to the ground from behind. His knees hard against the ground. The schoolyard bullies had nothing on his brothers though. The desperate fumble in the pocket of his shorts for his inhaler. The shape his mouth made instinctively around the coloured plastic. The strange sound of inhalation as a puff of medicine courses through his chest. A tiny moment of disorientation, a faint unsteadiness and then a sudden return to real time. The moment you allow yourself to understand that you are OK.

TY had this significant pre-existing respiratory condition, as well as cancer and was receiving immune compromising treatment. I’m not a medical professional but it would seem to me that TY should have been admitted to hospital as soon as he received a positive Covid test or at least checked by a GP. I recently read an account of Tom Daley, a white, British Gold Olympian athlete’s experience of Covid. He had a preexisting chest condition and was taken immediately to hospital when he received a positive Covid result. He is certain that is why he is fit and well today. When TY began to feel ill I urged him to contact his GP and cancer nurse. TY was reluctant to bother his GP (they’re overstretched as it is, he told me) but eventually after repeated requests he did. TY, a working class man of colour, couldn’t get past the receptionist who told him he needed to be tested for Covid and if it was positive to stay at home. His cancer nurse suggested the same and advised him to call the hospital’s cancer care hotline for patients. In the late hours of August 10th 2021 I would call the ambulance that would take TY from his rented room to the Intensive Care Unit at his local hospital, from which he would never return.

Who will be the clerk?

On July 31st 2021, the day TY received his positive Covid test, The Guardian reported that UK MPs had, “enjoyed a bonanza of free tickets this summer worth more than £100,000 from gambling, drinks and sporting companies as they took advantage of the government’s Covid pilot scheme for large events.Cabinet ministers Ben Wallace and Brandon Lewis, plus the opposition leader, Keir Starmer, were among those who benefited from free tickets declared during July, with more than 35 MPs in total accepting hospitality as they took part in the research project. With large events banned for more than a year due to Covid rules, MPs appeared keen to make use of the pilot scheme as they took up free tickets to the Euro 2020 football, motor racing at Silverstone and Goodwood, tennis at Wimbledon, cricket at Lord’s, Rugby League Challenge Cup, and the Brit awards.”

The summer of 2021, whilst TY lay dying, the US finished withdrawing from Afghanistan, all the while peddling the line that it would take several months for the Taliban to establish control. As it happened, the Taliban established control well before the last US plane departed on August 30th. The US based NPR would later offer a comprehensive timeline of events and report that, “U.S. Central Command Gen. Frank McKenzie announces the last planes have departed, marking the end of the military evacuation effort — and America’s war in Afghanistan. The Taliban celebrate what they call “full independence.” And for many Afghans — especially those wanting but unable to leave the country — a new era of painful uncertainty begins.”

Who will be the parson?

August 5th 2021 and TY messages that he has a nagging cough and temperature. I hear it when we talk. He is struggling to catch his breath. I suggest visiting A&E and he rejects the idea outright – the queues, the stress, the other things he could be exposed to and pass onto his Dad. I send texts to remind him to drink water and rest, as if this will somehow act as a talisman and ward off the possibility of what we both feared but couldn’t say.

August 8th , TY writes that he has taken another test in the hope that he is clear of Covid. He wants to show his anxious landlady that he is recovering. He tells me he can’t read the test. I ask if he can’t see properly? He types back, ‘Dunno’. I feel the fear tighten in my chest. I asked him to video chat so that I could read the test for him. He says he’s tired. I let him sleep.

The next morning he tells me that his worried landlady has asked him to relocate to a hotel room. I am livid. TY is calm. He says it’s because he has to share the bathroom with her and her lodger and she can’t keep cleaning it after he uses the bathroom. TY thinks if he can get a negative lateral flow test she will back down and he can stay. He is stressed and exhausted yet tries test after test. They all come back positive.

I ask TY again for friends and family and medical contacts. He says he doesn’t want his family to know and that there was no point telling friends. I ask him to please go to the hospital. He gets upset and angry with me. I feel guilty and back off.

August 10th TY is behaving strangely. He doesn’t immediately respond to messages and calls which is unusual in our relationship. I try calling and don’t manage to get him until the afternoon. He sounds different. As if he is distant and daydreaming. He loses track of our conversation. He says odd things. I ask him if he has spoken to anyone recently or if his friends have contacted him. He says no. I bring up the hospital again and he cuts me off saying that he has been speaking to his friend Del and it’s all OK. I’d never heard of Del before and when I enquire further he drops his phone on the floor. We have a strained conversation where I am repeatedly asking that he picks up the phone and he is using a strange childlike voice saying he just can’t reach. I stay online concerned that he is having a breakdown. Eventually he picks up the phone and says he doesn’t feel well. I ask him to get his landlady. He refuses to. I ask him to call a local friend. Who he asks? Who? Anyone I tell him, anyone – Del? He laughs. I ask him why he is laughing and he says Del is a voice inside his head. I tell him that I am going to dial 999 and call an ambulance. He gets distressed and begs me not to. I ask him to video call. He does. I look at his face, it is so clear that he is deeply unwell and can barely breathe. I know that I have to make the call and I do. I wait with him for the ambulance. He becomes progressively worse. At times he is shouting out angrily into the room saying he doesn’t want any ‘bloody randoms’ disturbing him. I’ve never heard him like this before. At some point he drops the phone and I am cut off. I try calling but he doesn’t pick up. Only later do I understand that the lack of lucidity is probably due to TY’s low levels of oxygen.

That night my five year old son is unable to sleep so I find myself wide awake and calling TY’s phone in the middle of the night hoping he will answer. I called the ambulance hours ago and had assumed he had been taken to his local A&E. He fails to answer and I start calling London hospitals to find out where he is. It’s not until the morning that I finally discover that he is on a trolley in a corridor waiting for a bed in the ICU. On the evening of August 11th I eventually manage to speak with TY and the medical staff who are looking after him. I learn that he has Covid related pneumonia and that his oxygen levels were dangerously low. I am made aware that he would have died had I not called the ambulance when I did. I speak to TY and he sounds terrified. He is frightened to be in the ICU. It’s a noisy place and he is on oxygen and rigged up to various, loud apparatus that are stopping him from sleeping. He asks me repeatedly when he can leave. He has been in hospital less than 24 hours.

I tell him he is precious. I tell him I love him. I tell him he is in a safe place. That he will be well. He calms. I ask for his family and friend contacts. He ignores me. I try to speak to the hospital staff. They ask who I am. I can’t sum up our relationship in a noun that is adequate and say I’m his friend. The nurse tells me abruptly that she can only speak to family or next of kin. I am devastated. I speak to TY and he tells me I am his next of kin. I ring back and let the hospital staff know that. Later a doctor calls me and talks through the realities of TY’s condition. I am told that his oxygen levels are critical. That he needs to spend time on the CPAP machine. The doctor at this stage is cautiously optimistic. He asks if TY will be returning to me when he leaves the hospital. I explain that I am hundreds of miles away and that TY has cancer and ADHD and ongoing psycho-emotional health issues and that his housing situation is currently precarious. He asks if he has any family to go home to. I tell him he is estranged from his family and doesn’t want them involved. The doctor says he will get the nurse to talk to TY and perhaps a social worker could help secure housing for TY.

The next day TY and I speak and he sounds overwhelmed, confused and vulnerable. He claims he is well and doesn’t have pneumonia. After our conversation I text him:

“How are you doing TY? You are in my heart & thoughts. TY, we just spoke a few minutes ago and you sounded confused. I just want to write here what happened over the last few days so you can understand what’s happening. You have been ill since the end of July. You thought you were getting better. But then you took a turn for the worse. You told me that your landlady asked you to leave and go to a hotel as she was concerned about catching Covid. You started to not make sense when we spoke on the phone a few hours prior to my calling the ambulance. I rang the ambulance because I care for you deeply and was very frightened for you. I am glad I did. I spoke to the Dr and she says you have pneumonia. Covid related pneumonia. That’s why you are on oxygen. She says they need to monitor you closely. I just spoke with the nurse on the ward and she is confused because you have told them you are alright and have a secure home to return to. I am only thinking of you and your needs and trying to advocate for you so when you leave hospital you will be well supported and in safe and stable housing where you will not be asked to leave if you are ill. All you need to do is concentrate on getting well, resting and accepting support that is being offered. I think as well as being physically ill you have and are having mental health issues. Which is understandable because you have been experiencing so much stress. You may not be aware but I hope you can trust me when I tell you that when we have been speaking you have not sounded mentally well my love. Which I totally understand as this is a huge life event. I also don’t think that you fully appreciate how weak your body is and immune compromised due to cancer. Which means that Covid is having a much bigger impact. Sending much love always. I hope you can accept help and support and rest and get as strong as possible. I also think your ADHD is full on at the moment due to stress. Which is so understandable. Please let me know if I can reach out to friends and family for you.”

The next few days TY’s messages consist of asking when he can leave the hospital. He tells me he can’t understand the medical staff because he can’t hear them due to the noise. I spend a great deal of time calling the unit to try and pin down the right person to speak with. They are busy and I get passed from pillar to post. I eventually speak to a nurse who says that TY is in her care and explain to her that it is important that the unit understand that TY has ADHD and is having difficulty hearing them and understanding what is going on. I ask if they could take time to explain to TY what is happening.

We revisit the question of next of kin and I ask TY if he wants to switch to his family. He says no. He tells me he wants me to be his next of kin. I try to broach the subject of his emergency medical preferences eg DNR and if he has a will. He says he will think about it and get back to me. He never does.

Who will make the links?

Friday 13th August and TY is still struggling to rest on the unit and tells me he is on 70% oxygen. He has physiotherapy and tells me that he is exhausted but still asks if he is allowed home. The next day I speak with yet another doctor – I never speak to the same doctor twice – and realise that they are under the impression that I am in London and will be taking care of TY when he leaves. I find myself repeating the situation and stressing the need for support for TY. I mention again the need for mental health support. The doctor tells me that that isn’t something they would offer at the ICU. It may be something that could be arranged for TY when he moves onto a regular ward.

TY and I text and have a difficult moment where TY is insistent he should be discharged and that he has a support network to return to. When I question this he says that he’ll be OK and tells me that mental health in his family is not recognised. August 14th he writes that:

“No one has ever spoken about mental health in my family.

Not when Mum died

Not when my brother died

Not when we got thrown out of the house at 16…

When G and M had their alcoholic/cocaine breakdown the best T could say is ‘What will we do with them?’

They don’t recognise it (mental health)

And they don’t deal with it…”

He tells me that when he finally leaves the hospital he wants to change his life. I support and encourage him and remind him that it’s OK to ask for support, He says he will and then says “How has your day been? Feel like I haven’t asked for ages?” I tell him not to worry about me but to focus on getting well. The next day, August 15th, he sounds brighter and tells me he is feeling better and needs less oxygen today. August 16th he writes again asking when he can leave as he is convinced he can recover at home. I gently remind him that the NHS has no desire to keep him longer than they need to and that his life is precious. This is the first day he specifically mentions the difficulties he’s having with the CPAP machine. He is severely stressed and anxious, and writes, “Don’t know if you ever used one but it’s horrible.” He tells me that I saved his life and thanks me. I tell him he has no need to thank me and that I love and care for him deeply. He showers me with heart emojis. We speak again later in the evening. I send him an article from the Guardian newspaper about Afghan women having to burn all evidence of their education and modernity, burning pairs of jeans and hard earned certificates. We discuss how heartbreaking it is. At 9pm I send him links to a Men of Colour mental health support group that a friend has kindly told me about. I sign him up for newsletters. He thanks me and says he will try it out when he leaves the hospital.

On Tuesday 17th August TY tells me that he could be moving to a new ward later that day. He is upbeat and says he wants to see the new Jordan Peele film with me when we meet again. We make future plans. The next day he still hasn’t moved ward but is under the impression that he would be later that day. He tells me that he is feeling better and ‘improving’ yet in a text a few minutes later he tells me that he “had a coughing fit for about an hour this morning” and was left exhausted by it. He has another in the evening and tells me that the ward move is now off the cards. It is the 18th August and by the evening I am texting him to apologise that I couldn’t uplift him better and that depression had settled over me. He texts, “You’re always there for me and you saved my life. I couldn’t ask for more.”

August 19th and TY is struggling with breathing. He mostly texts because it is physically exhausting to speak on the telephone and the ward is noisey. He refers to an X-ray he has been shown that indicates an improvement but he says that he still feels unwell. The next day he tells me that he has seen two doctors and they contradict one another. One says he is ready to be moved onto a ward and the other says he is still very unwell. TY is frustrated. He doesn’t know what is going on. He messages early on the 21st August and tells me he slept well because he asked for sleeping pills. At lunchtime he messages to say that he has been coughing violently. There is talk of a chest infection. Mucus cultures are taken. His last text that day reads “You mean a lot to me RM. I love you.”

The next day TY writes and says that the CPAP machine triggered a panic attack and that he started weeping in front of the doctors. When we speak he tells me how the machine reminds him of being jumped by his brothers and strangers at school. That he feels terrified and that he can’t do it. I contact the unit and eventually get through to a doctor who says that TY needs to continue with the CPAP machine. I tell him that TY is having panic attacks and being triggered by past trauma. I again request mental health support, someone who could help him talk through his distress one to one. The doctor tells me that the mental health team does not attend the ICU. He asks me if I am prepared to make decisions for TY as next of kin, in the event he can’t make them. I am stunned into silence.

Sunday 22nd August we message throughout the day and I reassure him that he is loved and in my thoughts. In the evening I broach the question of medical decisions and wills. TY tells me again that he can’t think about it right now but he will. I have a difficult night and in the morning when we connect we share how we are feeling and encourage one another. Tuesday 24th August TY tells me he is severely tired and breathless. He writes that when we meet he wants to use cannabis and get high together. He has never suggested that before. I ask him why, although I think I already know why. He writes, “Just want to feel different for a day at least.” We discuss his experience of the CPAP machine again and he writes: “It’s restrictive. Covers your face and mouth. Reminds me of being bullied by my brothers and when I was at school constantly being grabbed and people trying to crowd your face. It’s horrible. Doesn’t matter they are doing it to save my life here. Still feels the same.” I ask him if he has told the medical staff. He says not verbally but that he panics and gets upset every time he tries to use the machine. He tells me that this experience will stay with him. He is on 95% oxygen.

Wednesday August 25th and TY is given high dose steroids and tries but fails to use the CPAP machine. I call many times to speak to the medical staff. They’re all very busy but eventually I speak to a nurse. We discuss CPAP and I explain the trauma. She seemed to be unaware of this and the fact that TY has ADHD and mental health issues. I ask her to please make a record of this in his notes and ask if they can support him to feel better about using the machine. She says they’re very busy but will do what they can. The morning of Thursday 26th August TY and I speak and he recognises how difficult I am finding the weight of decision making, particularly because he wasn’t able to tell me what his preferences and requests were. He said he didn’t want to think about it and that the staff were also asking him as there was talk of intubation. He tells me that he has decided to make his estranged brother M his next of kin because the decision to be intubated needed to be made. He tells me he loves me but doesn’t want me to feel the burden. We cry together and I ask if he is sure. He says he has asked M to make all decisions in consultation with me. He creates a family whatsapp group and I meet his family for the first time this way. His first group text is “Raman saved my life… I love her. Please discuss all decisions with her and make sure you keep her in the loop.” Later in the same chat he asks his brothers if he could speak to his father. They discourage him immediately. They tell him he’ll be fine and that if he spoke to his Dad it would only worry him. In the event, TY never got to say goodbye to his father and I wonder where his Dad thinks TY, his son and carer, is. Does he think he has been abandoned by him? Thoughts like these press against my lungs and make it harder for me to breathe.

Things move quickly. In the morning there is a possibility of TY being put into an induced coma and intubation later that day. By the afternoon TY has decided that he can’t tolerate the CPAP machine and wants to be intubated. I talk to him and send him links about the realities of intubation but he asks me to stop. I understand his fear but am terrified he isn’t well enough to understand what a serious procedure it is. He tells me not to worry and that the doctors have reassured him it would be 5-14 days maximum, just enough time to allow his body to heal and that he would be woken up after that.

In the afternoon TY mentions his (half) sister, N, for the first time in a long time. She is white and has just contacted him after finding out he is ill. TY had told me about her before. Of trying to connect with his sister, trying to generate something. Taking her to see If Beale St Could Talk and her emerging baffled from the cinema. When TY tried to discuss the film with her he said it hurt him because ‘she just didn’t get it’. He said that was the last time he tried to talk about his experiences as a man of colour with her. When TY showed allyship with the BLM movement he found it odd how quick she was to virtue signal by putting up BLM logos and Black power fists on social media but was unable to have a conversation with him or make time to understand his lived experiences as a man of colour.

At 17.12pm TY texts me to say he has made the decision to be intubated that night. We speak with one another on the phone. We continue messaging after speaking to one another. At around 8pm he sends me his friend S’s number and asks me to contact him and let him know what’s happening. I tell him I am happy to do so. At 22.03 he texts “I love you. I’ll see you in September RM. I love you.” at 22.04 he writes “I’ll call you the day I wake”. I send a flurry of texts to TY and he answers them all and at 22.10 he writes, “Drs are here so it’s gonna be busy.” It’s the final words he says to me. I write back immediately “You are loved. Don’t worry about anything. I am with you.” He sends me a kiss and heart emojis. That is the last communication I have from him.

I find myself texting him every day. I keep a diary for him counting the days he has been intubated. TY dies on the 6th day of intubation when his breathing apparatus is switched off by his family. I have no say in the decision. In between intubation and TY’s death I find myself locked out of the information loop. When I called the hospital on the 27th of August to check how TY was doing, a further layer of hell state emerged. I am unable to get any information from the staff. I am not viewed as a valid member of his biological or nuclear family. I say that I was his next of kin and that although M, his estranged brother, was now named next of kin, TY had wanted me to be kept informed. The staff are firm that as I am no longer next of kin I can not receive information.

What/who is kin? What/who constitutes a family? A coincidence of biology or? How do systems like the NHS recognise family? Do these systems have the capacity to recognise the diversity of chosen family structures? If you deviate from the perceived norm you are invisible and this is the case for most Queer or non western structured families. Only those constellations recognised as ‘normal’ get to have agency in grief or otherwise.

I message on the family group chat, asking for updates. On the 28th TY’s brother M finally says that he has spoken with the doctor and that the doctor had requested that he go into the hospital in person. He said that he planned to go the next day. I immediately ask if TY has deteriorated and I leave a voice note which I ask M to play to TY when he visits, he never does.

I ask again for updates on the 29th August and receive no news. On the 29th I reach out to TY’s sister, N, asking for an update. I try the hospital again and manage to get through to a nurse who had spoken with me previously when I was next of kin. She tells me that TY’s brother M had expressly asked that I was not to receive information and that if I turned up at the hospital, I should not be allowed access to TY. I ask if M has visited. She tells me that no family members have visited yet. She sends me a video link so that I could try and see TY. But it repeatedly fails to work. I am, understandably, highly distressed and can’t quite comprehend what is happening. A few hours later N, TY’s sister, leaves me a voice note. She says she doesn’t want to get involved but knows what M is like. N tells me she intends to visit TY tomorrow. I ask if she would kindly play the voice note I made for TY. She says she will. In a moment of solidarity I share pictures of TY with her. Pictures where his face is full of pleasure looking at me, smiling, his eyes bright. I find myself sharing screenshots of some of our private texts as I feel the need to prove that TY definitely wanted me to be kept abreast of and included in all decision making. She doesn’t comment on the screenshots but asks me not to publicly share the single photograph she sends me of TY.

I try to organise visiting TY in hospital. I contact the hospital to try and speak to the sympathetic nurse. I tried several times and leave messages but can’t reach her. I don’t know what to do. Should I organise childcare and get to London or would it be a thwarted visit if I have no access? Later that day I received a sharp, formal text from N asking me to stop calling the hospital.

Who will mourn TY?

July 25th 2021 TY woke thinking of his Mum, Olive, who died when TY was 10 years old. He sent me photographs of his Mum via messages. We ended up exchanging photos from our childhood with quiet, comical references – ‘Me as a zealous, religious convert’ – I label a picture of an 8 year old me, veiled and ready for the Gudwara. TY doesn’t miss a beat – ‘Me as a terrorist’ he pings back alongside a picture of himself as a cute little boy with a backpack.

TY’s Mum, a working class woman from Lancashire already had a daughter from a previous relationship when she met and married the charming Afrose. TY shares a sweet snap of their wedding and the cake cutting ceremony. Olive, who looks full of life as a young woman, soon diminishes as a mother to 5 mixed heritage boys who would run her ragged and to whom she would eventually snap in her exhaustion and the disappointment in her failing marriage, “ Shut up you stupid Pakis!”

TY has little memory of this. He reads about it in an old diary that he finds in his Dad’s house that belongs to his brother G, who died of a heroin overdose some years ago. He does remember how ravaged his Mother looked before her death. She had chronic rheumatoid arthritis. On the night of Olive’s death, a 10 year old TY witnesses his Mother go from an over-extended housewife and mother of 5 young boys with not a moment to herself, to a barely lucid woman a few hours later. She dies in hospital within hours. Years later he understands that she died after accidently bursting a cyst whilst cleaning her ear with a Q-tip. The cyst turned out to be meningitis. His father would later mark the time of death in his diary. TY shares a photograph of the entry with me.

On July 26th 2021, TY was at his Dad’s house caring for him and sent me a photograph of another diary entry from his father’s diary – wryly commenting, ‘it only took him a mere 6 months to decide to send us away after my Mum died’. TY and his brother B were sent away to a residential school until he finally dropped out of education. The state boarding school was another source of trauma. TY was bullied and here was the place of his vivid memories of being jumped in the dark, strange hands covering his mouth and nose, while he struggled to breathe.

Of all 5 brothers, only Q, the eldest, managed to benefit from an education as a child. TY tells me he suspects that all his brothers, bar R, are on the spectrum and struggle with varying experiences of neurodiversity and ADHD. He says as he understands himself better he sees it in them. He tries to talk to them but it’s never any use and it leaves him feeling bereft and broken. He feels that he is frequently the butt of their personal frustrations and has spoken of bitter and cruel words being exchanged. Things that you try to forget but never can. He is particularly tortured by his brother M whom he encounters regularly at his father’s house and who he referred to as evil. I took it with a grain of salt at the time – knowing full well that familial discord can be profoundly wounding. TY had shared with me stories of sexual abuse in his family and had repeatedly told me that he wanted to leave London and his family behind. That he was committed to being there for his Dad until his death, but after that, he planned to move away, possibly to Glasgow and start a new life. He told me he had no intention of speaking with his brothers again. They brought him down and made him acutely feel the epigenetic trauma that they were all drowning in. TY felt he was the only one who got what was going on. He often rang me distressed after another run in with his family. TY would say to me in varying states of despair – “Can you believe I grew up with no intellectual stimulation?” He loved his brothers and father, despite their callousness towards him but felt that they constantly underestimated him. He frequently felt patronized and undermined by them. He complained that they regarded him as an errant teen.

It’s on this day that TY gathered items belonging to his dead brother G. He wanted to use them in the documentary film we are making. We discussed his ideas and shots and the possibility of acquiring a cheap gimbal for his camera. On his way home he told me he refound a restaurant he visited a few weeks back – “the tarka dhal is so good!” he messaged. Later he told me that no one in the restaurant is wearing a mask.

TY makes plans to visit me in Scotland and sent me links for the Glasgow airbnb he had booked for August. It is on the fourth floor with stairs and he worried that as I have an auto-immune illness, I will struggle with the stairs. He is keen to make plans for my upcoming birthday and suggested booking something now. I asked him to hold off as I wasn’t sure what my plans were at the moment.

On Jul 27th TY sent a link to the Black aboriginal comedy he had been watching and which he finds ‘hilarious’. We enjoy watching things together and through the pandemic we met regularly over the phone and online to stream plays and television drama and comedy like I May Destroy You and Man Like Mobeen. We would also read to one another. One of his favourite books was Harold Sonny Ladoo’s ‘No Pain Like This Body’- a text that he felt made him finally understand his father and some of his experiences. Later that day TY, who had been kicked out of his Dad’s house by his brother and has been renting rooms in shared houses, tried to sort out his housing application details with his local council. The application that he had submitted years ago was nowhere to be found online. He spent hours trying to negotiate the kafkaesque bureaucracy to get back on the housing list.

TY complained of feeling exhausted. I ask him to rest to consider an extended leave of absence from his job. He was worried about money. I asked him to consider PIPP or Incapacity Benefit – the thought of all the bureaucracy puts him off. He sent heart eyes and said he couldn’t wait to see me soon.

On July 28th 2021 TY messaged saying that he wanted to buy me a special birthday cake for my forthcoming ‘big’ birthday. He asked me to send suggestions of what I like. I sent instagram links for lush vegan bakes and we agreed that if he did buy one it should be from a Black or brown owned business. As usual we messaged throughout the day, his low energy levels are palpable and at 15.58pm he wrote, “I have so much to say but I’ll save it for when I’m with you next month”. I encouraged him to rest.

July 29th I messaged him in the morning and he told me he managed to sleep 7 hours straight and was feeling better for it. He suggested speaking on the telephone. I was in the midst of a low mood and the beginnings of a familiar depression. I felt phone phobic and sent a voice note saying perhaps tomorrow. He worried and left me several, sweet, encouraging voice notes – his voice tender and with a hint of something snagging at his breathing – perhaps an early sign of Covid?

July 30th, TY called me from the Lambeth Archives where he was researching Black and brown British history and said he felt awful and couldn’t concentrate. He thought he had a chest infection but didn’t think it was Covid because he still had his sense of smell and taste. I pressed him to take a test. TY took a lateral flow test and got a negative result. I was still worried and encouraged him to go to his local Covid test centre and get a PCR test. He did. On July 31st his test results came back positive. He bunkered down in his small rented room. I was concerned and asked him to check in with me every 2 hours. He downplayed the result. Said he is fine and batted away my concern. He was worried about who would take care of his dad. We talked about delegating to his family but he was reluctant to have any contact with them. I sent him a screenshot of advice for cancer patients with Covid, he said he’d read it properly later.

Who will carry TY’s coffin?

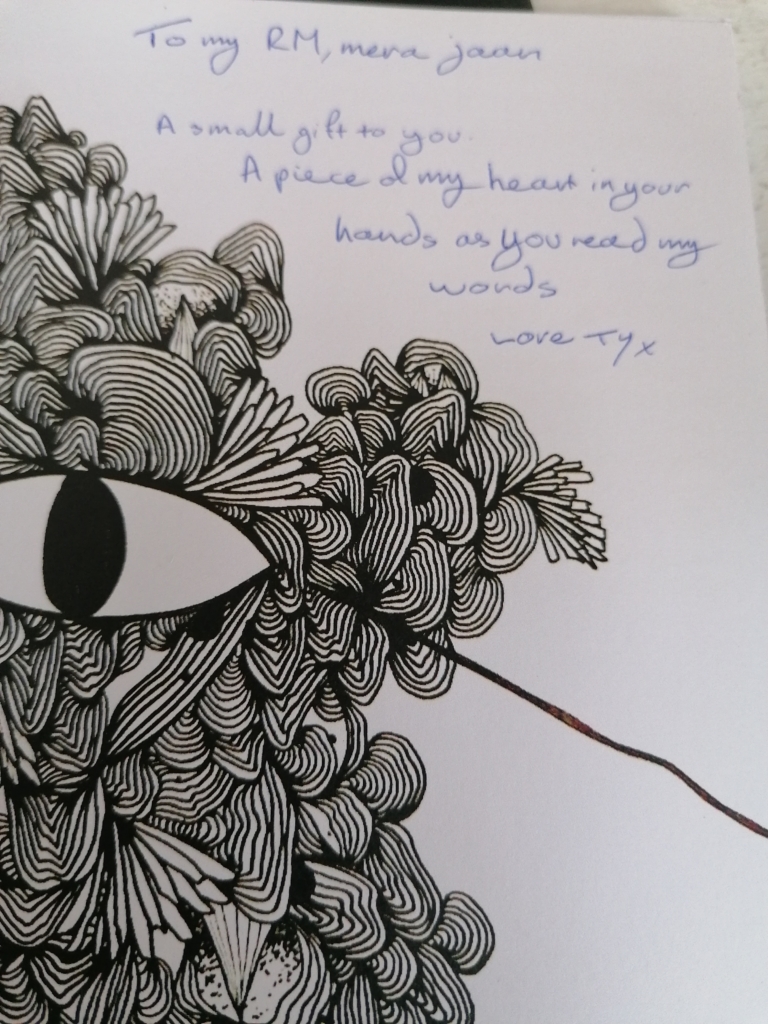

TY is one of the Black and brown students featured in an anthology on mental health. He was proud of being featured in it and gave me a copy inscribed – “To my RM, mera jaan – a small gift to you. A piece of my heart in your hands as you read my words. Love TYx” His contribution is entitled ‘Who Am I?’ in which he writes:

“So, who am I? An Aristotelian axiom suggests that “you are the sum of your parts.” Like [Samuel Dixon] Selvon, I am made from various parts. I grew up in a white working class…East London. I spoke and dressed like everyone else. Yet more than occasionally I was reminded that I wasn’t the same. In the good old days they used to call me Paki; now I am apparently a member of ISIS…I am a – Lonely – Londoner, and I am of northern English heritage from my Mum’s side…and I can trace my mum’s family back to the 15th century… on my dad’s mother’s side my cousin has traced our family tree seven generations back to a husband and wife from pre-partition India in the Punjab area…The question remains, who am I?…Some white people don’t accept my Englishness because I have brown skin. When I talk to Indian Caribeans they sometimes talk to me as if I’m an “English boi,” but then a brief encounter [with] Guyanese writer and publisher, Arif Ali said to me, “O, you’re a coolie boi, welcome! While some Indians and Pakistani professionals and academics that I try to connect with seem to look straight through me, as if I don’t exist; can’t exist. So who am I? … The rupture of my Indian Guyanese identity started with my family not discussing our heritage and continued with the experience of racism from my fellow Londoners… The media and political class tells me I must integrate but doesn’t allow me to do so. While I may not be able to bare my fragile soul and declare my vulnerability, I can say that my inability to previously identify who I was and where I belonged, racially and socially has affected my mental stability to the degree that I asked the NHS for help. This ongoing state of precarity continues to make me ask, “Who am I?””

An article in The New York Times confusingly titled ‘Indian, Twice Removed’ features interviews from Indo-Guyanese who have settled in New York – “From my experience, we’re not Indian,” said Latchman Budhai, 56, the former president of the Maha Lakshmi Mandir, a Hindu temple in Richmond Hill whose members are almost all Guyanese-Americans. “We look like Indian, but we’re not Indian. … Some Guyanese talk with hurt about not quite being accepted as Indian. Mr. Budhai recalled how in 1978, his wife, Serojini, won an Indian beauty pageant but was never awarded the top prize, a trip to India, after the organizers learned she was Guyanese.”

Yet Indo-Caribbeans are not the only group of Indians stolen from their homeland and transplanted to provide labour for white people and western economies. In Cape Town, South Africa, the first Indians arrived during the Dutch colonial era, as slaves, in 1654. A conservative calculation based on records shows over 16,300 slaves from the Indian subcontinent having been brought to the Cape. In the decades 1690 to 1725 over 80% of the slaves were Indians. This practice continued until the end of slavery in 1838. I have experienced the cultural amnesia around this forgotten and hidden part of African, Indian and European history in person during my visits to Cape Town. The Capetonian Slave Lodge Museum features a small board that could be easily overlooked, relating these historical facts. Equally the ground breaking and culturally significant District 6 Museum had nothing related to this history the last time I visited a few years ago.

Because the South Asian experience of slavery and indentureship is so little known it is difficult to find a language to speak about the impact this history has. And how this experience sits beside Black communities and their lived histories. Of course the experiences of Black people are different – and sadly include prejudice from brown communities. That truth exists alongside the possibility that we have more in common than not. In solidarity with one another it may be possible to gain an understanding of how colonialism and colourism have been seeded in us and used to separate us. Without unity we will continue to be riven by the ever effective divide and rule tactics that sustain whiteness, white supremacy, neo colonialism and capitalism.

TY wanted to tell his family story, his own story, the Indo-Caribbean story but was unsure how. He was trying different methods. He returned to education and was inspired by new ideas of seeing and understanding the world. He was excited by and enjoyed reading the words of Franz Fanon, Hélène Cixous and Édouard Glissant. He loved the stimulation of reading, dialogue and art. Through engaging with these texts he began to understand his own life and how racial, historical, societal and cultural contexts shape lived experience. Through film. Through performance. Through dialogue. Through theatre. Through scriptwriting. The more he began to understand his own familial legacies, the more he tried to somehow make sense of the trauma and of the sadness, the cycle of fucked-upness, the repetition and never-ending ferris wheel of his life with its inevitable stuttering halts at various heights.

I encourage him to take his dead brother’s things from his Dad’s house and bring them on his visit to Glasgow. We talk about my filming and directing him whilst interviewing him informally about the things in the bag and what they brought to mind. Where they take him emotionally. What this detritus of life hoarded in an Indo-Caribean’s octegenarian’s East End house could mean. I tell him to take a taxi home – did the driver wear a mask? I remind him to eat. Ask him if he wants me to organise a food delivery. TY tells me not to worry and that he has frozen food. At some point in the day I ask him how he is physically feeling, specifically his chest. He writes, “apart from occasionally coughing my breathing is fine.” He tells me that he has had an encounter with his oldest brother Q, who has rigged his father’s home with security cameras and maintained a ‘big brother’ watch from afar. ‘What happened?’ I ask, sensing the pent up anger straining in between the ellipses as he types his texts.

TY tells me he was berated by Q unfairly and disproportionately for a minor mishap, it has brought him down. I leap into protective mode and reply that his brother is an uncompassionate, smug prick. TY says again, something he has often said after yet another emotionally erosive experience with his family – “They don’t listen. They never do. They haven’t listened to anything I’ve said. They never have.” TY felt unheard, unseen, unappreciated and unknown by his family and frequently by his friends. He wanted to feel the warmth, safety and encouragement of family and friends. He allowed himself to feel it in our friendship only to frequently jolt and rear up at the unfamiliar emotional landscape. He was adept at throwing metaphorical grenades into our ongoing relationship. Testing and pushing me to assert boundaries between us. I refused to be his one-person support system. I’d been there before and I knew it wasn’t sustainable. As usual we speak about other potential support in his life – another informal audit of the relationships in his life.

We don’t name it but a familiar sense of blooming isolation was enfolding in his heart. His vulnerability lingering like a heavy scent between us. I am in Glasgow, I am a mother of three, young children. I have my own stuff going on. I feel a rush of anger towards his London friends, like the older, Black gay man, S, whose intelligence, creative achievements and confidence TY admired and who affirmed TY’s lived experience as a brown working class man of Caribbean heritage, and regaled him with vivid stories of his sexual exploits in Finsbury Park. When I asked him why he thought S felt the need to share such detail, TY held no judgement and told me that that was just the way it was. People told him things. People left things in his hands, on his lap, in his head. He was full of this congealed emotional residue. He was confused by their energies and expectations. He often felt like he didn’t ‘get it’. That he was on the outside of a conversation everyone else was fluent in.

Feeling unsure of how to make this right, how to hold him other than hearing him through our encrypted connection, I switch to parent mode, TY like so many of us hadn’t been parented well and I want to make him feel held and better. I want to do something practical and positive. Not knowing what that could be I suggest joining his local Mutual Aid group. I send him the link. He tries, unsuccessfully, to join via the facebook page. I encourage him to ‘bug them – let them you are in need, stress this’ I urge. When by the end of the day he hasn’t heard back from them, I contact them on his behalf via messenger. I don’t hear back from them either.

Who’ll bear the pall?

Inform your landlady and flatmate that you’re ill, I text, and ask them for help. He messages back that he had and they said they would check on him. Something makes me want to ask him for his medical details and emergency family and friend contact details in case of emergency – I don’t know why but I feel a distant panic. TY says he feels like his brain is fried at the moment and he’ll let me know in the morning. I tell him to rest. He continues to text late into the evening, unable to sleep. We speak briefly. He shares an old calypso song by the Mighty Dougla and texts “heard this on black audio (collectives) handsworth sounds – so cool!” “Split Me In Two”, is one of the Mighty Dougla’s best known calypsos, dealing with the Dougla’s position in the Black/Indian political division in the Caribbean and proposed repatriation (“I am neither one nor the other, six of one, half a dozen of the other, If they serious about sending people back for true, They got to split me in two.” It was yet another cultural mirror for TY, a rare space where he saw himself and his struggles.

Shubi Mangla defines Douglas (Doglas) as “ basically the people of mixed ancestry of Indians and Africans. In the secondary sense, Douglas, carries the meaning of an impure blood and calls the person an illegitimate child. The term originated from the Bhojpuri or Hindi word “Doogala”. Ferne Louanne, Regis of The University of West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago, writes that, “The word Dougla is linked to dogla which is of Indic origin and is defined by Platts (1884, p.534) as a person of impure breed, a hybrid, a mongrel; a two-faced or deceitful person and a hypocrite.” She goes on to explain how the meaning and experience of being a Dougla expands across the Caribbean – “In Martinique, people of mixed Indian and African descent are called chappè (escaped) or èchappè (escaped). Its literal meaning is a person who escaped from being a pure Indian. In Guadeloupe, these people are called batta coolie or batta-zendeyn, wherein batta means “bastard” but intends to give a sense of mixed heritage, rather than a negative meaning. Guyana has the largest population of Douglas.”

On August 1st 2021 I message to ask how he is feeling. He tells me he is feeling better and that he has solved the mystery of where he caught Covid. ‘Where?’ I ask. He is convinced it was at one of the local Indian restaurants he visited recently. He said at one he had forgotten his mask and at another the waiters weren’t masked. Mask wearing, unlike in Scotland, was not obligatory in public spaces in London. By this point there is a significant decline in mask wearing. I glance at the muted television news as I read TY’s messages. On the news Boris and his cabinet pottered around Westminster maskless. I text only half joking, “Please don’t be lax with your mask again…Basically it’s masks until we die! That’s how we have to navigate the world now!” He responds immediately, “I won’t ever. I will be wearing masks until I am 80 and pissing myself to death.” TY never knew he was just a month away from his death and that his 80 year father whom he cared for would outlive him, his youngest son.

TY was constantly looking for reflections for himself and was teaching himself Hindi. He introduced me to fascinating videos of Bhojpuri singing, a culture and history I was unaware of. After years of struggling to make sense of his relationship with his distant father – his ‘miserable old man,’ as TY called him, he began to recognise him as a person of colour and started to see his father’s life from that perspective. He found compassion for him. When his father was diagnosed with dementia and alzheimers, TY was quick to commit himself to the care of his Dad. He wanted to be there for him and look after him.

Frustrated with Brexit, the Conservative government and Westminster, he was interested and engaged with what was happening in Scotland. He was uplifted by the recent Kenmure St action in my local community and attracted to Glasgow and the activists he met through me. When the time came for his Father to die, he said more than once that intended to leave London and what he referred to as his ‘toxic family’ and move to Glasgow.

TY loved Indian food and the highest accolade was if it matched up to his aunties cooking. He enjoyed visiting the local Pakistani food shops in Pollokshields during a visit to Glasgow. He purchased a kitchen worth of spices and a tuva and spent his visit trying to conjure up his Auntie’s dhal roti – perhaps searching for his madeleine moment.

On the 2nd August, 8 days before TY ends up in the Intensive Care Unit and I am travelling with my family enroute to the Shetland Islands. I message TY from the ferry. Sending him screenshots of my location and journey overnight on the ferry through the North Sea. He is surprised at the distance and how remote I would be from the mainland.

TY was interested in performance and art. He was an avid fan of Genesis P’orridge and Throbbing Gristle. Once he sent me half a dozen links of his current obsession, a Bavarian fat positive performer – he told me he had been watching her sing on repeat and felt a visceral pleasure – ‘she is so beautiful’ I recollect him saying. He once fell head over heels with a performance artist and followed them on tour to Europe. He was so nervous to speak to them he drank to try and calm himself and ended up vomiting over them and their expensive, fancy coat. Needless to say he didn’t get that second date.

Whilst studying for his MA TY began putting together and hosting a fascinating podcast that interviewed artists, performers and live artists. Sadly, in a moment of depression he deleted and permanently erased the impressive body of interviews he had collected. Depression, anxiety and low mood was a recurring feature in his life. Something he spoke little about. I was privileged that he felt safe enough to share details with me. He spoke of a year abroad in Aarhus and falling into a crippling depression and feeling desperately isolated. He said he remembered stopping washing and cleaning himself and feeling like a living ghost. He would go on public transport and people moved to avoid sitting next to him because of his pungent odour. He said at times this rejection felt like it was the only proof he existed.

As a mature student he lived in halls of residence and felt lonely and disconnected. His distress was invisible to most as he appeared to be functioning. He would self harm in his room. Absorbed in cutting his feet and the tender skin between his toes, finding momentary relief from his psycho-emotional pain. He told me he once left to go to get some water from down the hall and had forgotten that he was barefoot and wearing sliders. It was only when a passing, young, fellow classmate gazed in horror at his feet that he realised that his bloodied feet were on display and how that must look to others. His classmate never mentioned it and neither did TY. He was attractive and had a warm personality and connected with people easily but rarely felt seen or that people had the time to hear him or support him.

He attended a Caribbean cultural group and got to know the Black married couple who organised it, one half of which was a woman called P. He considered them friends, but when it came to drawing support from these friends he drew a blank, feeling frequently fobbed off. Immediately after he died I was contacted by P. TY had regarded her as a friend but felt she had very little time for him. P told me that she sensed TY had needed more than she could give him. P said she felt that he needed parents and that she and her husband had somehow sub-consciously become TY’s parents in his mind. Later P would become part of a small group of ‘friends’ that would work with TY’s family to create a funeral that bore no reflection of the man I knew.

Who’ll sing a psalm for TY?

When P called me I shouldn’t have answered the call, I was raw, grieving and disorientated but despite this I speak openly to this woman, who I believe is showing me kindness. I want to feel connected to others who knew TY. I tell P I am worried that TY will have no legacy. That his wishes to have a muslim funeral won’t be honored. I tell P about what happened in hospital, the trauma around the CPAP and being locked out of the information and decision making loop. In my immediate grief I just can’t stop talking. I tell her about the film TY and I were making. That the footage was on his camera, laptop and phone and that I was worried that his family wouldn’t appreciate his things and that the footage would be lost forever. P was aware of the dysfunctional family dynamics and in fact referred to them as ‘addicts’ and asked if she could help. I said yes, perhaps she could make a massive difference by collecting this material and passing it onto me so that I could honour him and his creative intentions. She lived near to his address and said yes, she would be happy to go the next day. I was full of grief and knew from experience that communication with TY’s family was fruitless. Perhaps I was being ridiculous and naive. I genuinely thought at the time that P understood where I was coming from. I was thinking of things I’d read about the friends of Gram Parsons and John Barrymore – how unwilling to let their loved one be buried without properly honoring them, they had intervened in radical and extraordinary ways. I was thinking of what I could do for TY in death when it was clear that I couldn’t have any influence over his death rites.

The next day I received a terse WhatsApp from P stating that she had discussed it with TY’s close friends (who are these friends I wonder? Did they know he had cancer? Did they know he had Covid? Did they offer him shelter when he was homeless? A space to talk when he felt broken?) and they all agreed that what I was asking of her was illegal. The same day I receive a message from N, TY’s sister, saying that she was angry that I hadn’t contacted her when TY was ill to let her know. I numbly reply – How could I contact you when I don’t know you? I let her know again that TY hadn’t wanted his family involved. She suggests that I am somehow responsible for his death and that I should have tracked her down. I tell her I don’t even know her full name. I mute the messages. A few days later I pluck up the courage to ask her directly for TY’s things so that I could finish our film. She tells me that she had already been informed by P that I had made this ‘inappropriate’ request the day TY died. My legs give way with the pain and grief.

At some point a WhatsApp of ‘friends’ and N, his sister, had been set up. I was on it and I watched the funeral preparations enfold. I thought things had gotten as bad as they could be until a bizarre image of what looked like Golliwogs or at best, burnt gingerbread men was posted by his sister. They turned out to be TY ‘teddies’ she had made with TY’s old shirts, to be handed out as keepsakes at the funeral. I was horrified, it was clearly culturally tone deaf. I thought surely someone will point out the inappropriateness to this white woman. Instead heart and thumbs up emojis abounded. Several women, including P, praised N’s thoughtfulness. I felt physically sick. I also realised that they had already got access to TY’s things. TY had a sparse wardrobe and I recognised the shirts that were used to make a minstrel of him as a dead man.

TY’s circle of friends, all upstanding ‘good people’ police my grief. Deciding what is or is not appropriate. Curating a respectable grief where my ‘crazed grief’ and inappropriate requests are shunned and shamed. There are respectability politics in play with the shrinking of grief to a bite sized, orderly half hour service. A maintaining of a structured space that can’t hold the nuances or unruliness of grief and the necessary ritual it deserves. That won’t honour the dead but creates a manageable, caricature of them that holds no questions or self reflections. We learn nothing about ourselves or the dead. Instead we tacitly agree to a level of comfort that will deliver a place holder for an honest death ritual and remembrance. We sign up to play our part in this one off performance. I understood that there’s a show going on without me, regardless of me but more importantly, without the true spirit of TY. But who is this show for?

I’m not thinking clearly and I call S, TY’s Black gay friend hoping to find solidarity with him. I try to speak and say that I feel devastated by TY’s death and what was unfolding. My words don’t come out right. I feel his reluctance to engage, he orders a coffee whilst I speak, and very quickly the conversation takes a turn for the worse. I am snotty crying and probably being incoherent, trying to connect to this man, this stranger, who was loved and held dear by TY, and who was shouting at me to be quiet. Telling me that he would put the phone down if I didn’t shut up. I am triggered. It takes me back to the years of misogyny I have faced in my childhood home where a female’s voice and feelings meant nothing. The phone call ends with a flurry of recriminations and S shouting down the phone “You better be careful! You are alienating everyone!” I am shaken. After the call I pace my home and ‘speak’ to TY, I ask him what has he exposed me to? Who were these human beings who now presented themselves as family and friends?

A casual search online finds a variety of people mentioning TY’s death on social media. This is our modern, convenient way of expedient remembrance. Memorialising with candid pics and RIP alongside candles and prayer hands whilst broken hearts and weeping, waterfall eyes emojis and snappy condolence gifs abound. An old lecturer writes: “TY was an outstanding student gaining a distinction for his dissertation, a cultural studies analysis of the work of the Indo-Guyanese novelist Sam Selvon (The Lonely Londoners). This set him on a path of discovery of his own Guyanese heritage that he planned to realise with a PhD and scriptwriting.” This same lecturer TY told me had been less than understanding about his struggles with dyslexia and ADHD. A fellow student B writes: “Although a number of us knew him for only a few years and in some cases he met others just a few times…TY was one of those people who touched you and you knew he was going to be in your life forever.” There are others who write benign platitudes that make my blood boil – ‘He had so much to live for,’ ‘He’s in a better place,’ ‘It must have been his time – God needed him’- this sentimentality is reductive and belies the reality of his lived struggle. It particularly hurts to read the outpourings of public remembrance when I know that TY felt he couldn’t call on any of these people in his time of vulnerability.

I realised that I couldn’t attend the funeral – I didn’t have the strength nor did it feel right. It didn’t seem an appropriate place to say farewell or honour him. The funeral felt more about the family centering themselves than TY. I felt unable to be in a strange city and vulnerable and watch what felt to me like a bizarre performance of grief by people who were never really there for TY nor really knew the man he was. The final violence was seeing the private photographs I’d shared of TY being used to advertise the funeral and memorialise him. I felt it gave a false sense of TY’s relationship with his family. His face was not open, smiling and relaxed around them. I selfishly felt l that that face belonged to me.

Who’ll sing a psalm?

Perhaps this is an attempt to sort through my personal grief and anger. I shared with TY as much as I could but the unbearable truth is that he needed more than I could give him. Sometimes he railed against this fact and we had difficult moments but the love always remained. It was part of his ongoing struggle but he was trying. He was interested in finding a person of colour therapist who would be a good fit for him but struggled to access the support he needed. He was a beautiful, tender, complicated soul who needed a break. He was a human being in search of meaning and looking for community and connectedness and kinship with others who understood and appreciated his lived experiences.

Yes I know the facts. Black and brown people, working class and low paid, frontline key workers are the most vulnerable to Covid. Yes they are the equivalent of 2021 canon fodder. But how do I accept and live with this? What do I do with my anger? Everything was stacked against TY: from his night shift work on the frontline, his traumatised family, to his brown working class roots and ADHD; to his inability to access community, which in itself has been systematically been worn down by government after government. The legacy of colonisation and the gaslighting around it means that so many of us carry an active and epigenetic trauma that is not recognised in the white contexts we live in. How do I begin to understand this complex layered tragedy where even when we love someone and recognise their vulnerability and need for support, we live such atomised and individuated lives, are so drained by the hetero-normative, capitalist system we exist in, that we lack the energy or capacity to act or turn up for each other. Are we all ‘good people’ who are totally exhausted? Or, are we trying as best we can with interpersonal balms to remedy systemic and historical legacy and lack.

How do I place the fact that TY’s suffering and that his life ended prematurely and as a direct consequence of the intersections of oppression he faced as a working class, neurodiverse brown man? What do I do with the loss and keening inside my heart? Perhaps this is a eulogy for TY. The word ‘eulogy’ literally means ‘to praise someone’s life’. Alexandra Grace Derwent writes that, “From a spiritual perspective: the transition of the soul back to its source is assisted greatly by a good eulogy. Many traditions believe that the soul feels ready to go onwards once it has heard their life’s story told. …the process a family or community goes through to create the eulogy is also a process of coming to acceptance and release of that person. So writing a eulogy is a profoundly healing event.”

Who’ll toll the bell?

Tonight is the ninth night I have spent writing this for TY. TY is now a number, a statistic in this global tragedy – what a waste of life! I can not stop the tide of grief and the anger percolating within me – this was a preventable death. This was a complex and casual killing, a social and systemic murder of sorts. Why is TY dead? Why is TY dead?

Who killed TY?

With heartfelt gratitude to:

Chris Brown

Lisa Fannon

Martha Adonai Williams

Sabrina Henry

Ashanti Harris

You can follow Raman Mundair here:

www.rmundair.wixsite.com/website

twitter @MundairRaman Instagram @ramanmundair @rmundair

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.