Holding a fistful of pungent beige pellets, Ed Towers warns that those averse to garlic should stand back. The scent hits anyone within a few feet of him but rather than seasoning for the dinner table, these small garlic-infused cylinders are being fed to dairy cows at the Brades family farm in the verdant hills of the northern English county of Lancashire.

“We had been worried the milk would taste of garlic,” says the 29-year-old farmer. But, fortunately, “we’ve had no complaints,” adding that the cows seem unfazed by the powerful odour.

With climate change and the substantial greenhouse gas emissions from livestock coming under increasing scrutiny, many farmers and scientists are looking for affordable solutions that might make meat and dairy greener.

The garlic and citrus pellets used at Brades Farm are one such innovation: the supplements are mixed into the feed given to the family’s herd of 600 cows, and have helped reduce the volume of methane — a greenhouse gas and major driver of global warming — produced by the animals. The pellets work by disrupting methane-producing enzymes in the gut.

Towers says the idea of tackling methane emissions coincided with the farm’s launch in 2016 of its “barista” milk for cafés and coffee chains, when plant-based milks — which now account for 10 per cent of the overall UK milk and alternatives market — were beginning to persuade buyers to go dairy-free. While previous anti-milk campaigns have centred on health and animal welfare concerns, the focus has shifted to global warming.

The climate impact of agricultural sector emissions has been known for decades, but the role of livestock has come under increasing scrutiny only in the past few years.

“We were very aware of [the emissions issue] and we wanted to try and solve this,” says Towers, who runs the 380 acre farm with his father John. Even if they switched to electric tractors and used solar panels for energy, only half of the farm’s emissions would be eliminated. Then the family came across Swiss biotechnology start-up Mootral, which invented the pellets.

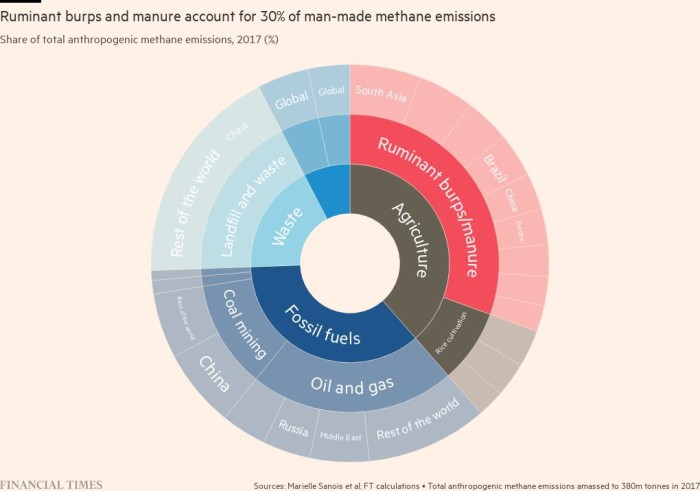

As the impact of methane emissions has become clearer, the dairy and meat industries are in the direct line of fire. Domesticated animals emit about 5 per cent of total human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, although that rises to 14.5 per cent when feed production, transport and other factors are taken into account, according to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization.

About 1.5bn cattle produce 7 gigatonnes per year, or 60 per cent of livestock emissions, with almost 40 per cent coming in the form of methane. Although it lasts for less time in the atmosphere, the greenhouse gas is about 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a factor in global warming.

Cows, and other “ruminant” animals whose stomachs are divided into compartments, produce methane during “enteric fermentation”, the digestive process as enzymes in their gut break down grass, hay and other feed. The gas, which builds up in stomachs, is then emitted largely through their burps.

Tackling the methane problem is both urgent and difficult. While carbon dioxide is “the most important” contributor to human-induced warming, methane is the next most significant, a report from another UN body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, concluded in August.

Agriculture is the leading source of global methane, accounting for about 40 per cent, the bulk of which comes from livestock. Brades Farm is part of a growing movement in the industry, with farmers and food companies competing to be viewed as green and responsible, by planting trees or switching to regenerative farming, largely focusing on natural methods to improve soil health and boost biodiversity.

“There are big climate risks for all of us if we don’t get on top of food system emissions,” says John Lynch, a researcher on the climate effects of meat and dairy production at Oxford university. Consumers in the west, especially the younger generation, are moving away from products with a significant climate footprint. “If the sector is not making serious attempts to reduce its impacts then it will start to lose its social licence,” he adds.

Biotech companies, scientists and farmers around the world are working to tackle the problem — to reduce emissions while retaining the level of agriculture needed to feed a global population predicted to grow by more than 2bn by 2050 according to the World Bank.

“Over the last couple of years [climate change] has just skyrocketed up farming’s agenda,” says Stuart Roberts, a crop and livestock farmer in Hertfordshire, north of London who is also an official at the UK’s National Farmers’ Union. “While we’ve got an important role to play in addressing climate change, we’re also probably the first industry to feel the effects of it,” with changing weather patterns already threatening crops.

From the lab to the field

Although plant-based alternatives are already gaining popularity, and start-ups are developing products made from animal cells and other micro organisms, scientists, entrepreneurs and food companies see an opportunity in producing methane-reduced meat and dairy.

Potential solutions range from new feed supplements, to face masks worn by cows. Another idea is simply to breed livestock that reach slaughter size faster — meaning they are around, emitting methane, for less time.

The Mootral pellets being used on the Brades Farm can reduce up to 30 per cent of the methane emitted by a cow, according to peer-reviewed studies. Thomas Hafner, a Swiss biotech investor who founded Mootral, says his vision was to reduce the emissions from livestock while offering a financial incentive for farmers, who often work to tight margins, to do so. “It’s about how farms can be part of the solution,” he says.

In Mootral’s research laboratories north of the Welsh capital Cardiff, head of biology Daniel Neef is looking for alternative ingredients to try and improve the effectiveness of the pellets. “Climate change isn’t waiting for us to find a solution,” he says.

“Cows and sheep have historically played an important part in our lives,” says Neef. Nutritionally, these animals have the ability to do something amazing, he adds: metabolise hay and grass, which have low-quality protein and are generally difficult to digest for humans, into high-quality nutrients.

The Swiss start-up, which expects to have about 20,000 cows in the UK and US taking Mootral by the end of the year, is not alone in seeking to improve the environmental credentials of cows through feed additives.

At the University of California, Davis, researchers have found that a certain type of seaweed in the cows’ diet can cut methane emissions by as much as 82 per cent, although seaweed production is difficult to scale up.

Royal DSM, a Dutch health and nutrients group, has recently received regulatory approval from Brazilian and Chilean agricultural authorities for its supplement Bovaer. It breaks down the methane into compounds already naturally present in the cow’s stomach, and trials have shown Bovaer to cut methane emissions by about 30 per cent for dairy cows and up to 90 per cent for those reared to provide beef.

Latin America, especially Brazil, accounts for a fifth of total agricultural methane emissions. The hope is that a low-cost additive, or another solution, will be found that can be used in developing countries, where the problem is particularly acute. Low- and middle-income nations contribute 70 per cent of emissions from ruminant animals, says the IPCC. Many of these states are expected to see a boom in their populations in the coming decades, and an associated rise in demand for food.

“One of the really big challenges . . . is to figure out [the] strategies for grass-fed cows in developing countries,” says Ken Alex, director of Project Climate at the University of California, Berkeley. The issue in these countries is less one of large farms, and more one of innumerable small herds that support a family or a village, he adds.

While laboratory studies and trials have been encouraging, researchers have had to balance any additive’s impact on animal health against the taste of the milk and meat. One enduring practical issue is how to feed additives to cows when they are grazing in fields, which is when they produce the most methane.

Dairy cows can be fed supplements in farm buildings around the time of milking, but the supplements cannot be sprinkled over the grass. Beef cows spend their time grazing at the start of their lifetime, and can only be fed the additives when they are in the feedlots to be fattened up. This stage only accounts for about 10 per cent of their lifetime methane emissions.

“Reaching the cow at the different times of their life is a challenge,” says Ivo Lansbergen, DSM’s president of animal nutrition and health. Hafner says Mootral is looking at giving the supplement in treats, which the cows can go and pick up, or a time release capsule which could last a number of weeks.

Some attempts have been criticised. In the US, Burger King last year faced criticism for trivialising the issue when ads for its limited edition “reduced methane” burgers made from cows given lemongrass in their daily feed, called consumers to “Breathe the farts of change”.

Other innovations include a methane-reducing mask for cows, trialled by Cargill, the leading agricultural and food group. Up to 95 per cent of cattle methane emissions come from the mouth and nostrils, and prototypes of the “wearables” developed by UK start-up Zelp, oxidises the methane, halving emissions, says Cargill.

Anti-methane vaccines are also being researched, while scientists and livestock genetic companies see breeding bigger cows more quickly as one solution to the emissions problem. Increasing productivity also makes commercial sense for the livestock sector, according to the NFU’s Roberts. Cows that live for less time will emit less methane, he says. “It is quite feasible to shave [three-to-six] months off the finishing age of an animal.”

Yet, the industry has been slow to act on climate change and there is a long way to go before methane-free cows graze in the fields.

“There is a fair amount of distance to go before there is a large-scale effort to make some definitive statements around what you should do [with] feed,” says Berkeley’s Alex. “One of the things that I’ve learned is you have to be very careful . . . These things that look very promising are [sometimes] not as effective for whatever reason.”

These limitations have generated criticism from those who see supplements as an incremental solution to, or a distraction from, a major problem.

“This smacks of the industry just trying to greenwash,” says Pete Smith, professor of soils and global change at Scotland’s University of Aberdeen, who believes that eating less meat is a more effective solution. A partial reduction in emissions from a small part of a cow’s life was “better than nothing”, he adds, but “it’s not going to solve the problem”.

“It’s not realistic to stop producing beef or dairy products when the population is growing. People in emerging markets are also moving from cereal-based diets to protein-based diets,” says Hafner, shrugging off charges of greenwashing. “If at the end of the day it enables us to make an impact, then we don’t care.”

‘The biggest responsibility’

Incentivising farmers, especially those in developing countries, to start using methane-reducing solutions will be difficult. Companies including Mootral hope carbon offsets might help farmers by generating credits, which represent emissions avoided or removed from the atmosphere, and sell them for cash.

Offsets are generated by activities including tree planting, carbon capture technology and even Mootral’s supplement, and are increasingly sought after by organisations aiming to compensate for their own emissions. DSM says it is exploring the launch of a carbon credit scheme to coincide with when its supplement hits the market.

Back in Lancashire, the Towers family says its quest for lower emissions has sparked interest from customers and fellow farmers. “There are a lot of people under a lot of pressure” to reduce their emissions, says Towers’ father, John. “Our industry is waking up to the fact that it has to change.”

The younger Towers says the switch to lower methane milk has been easier for Brades than it would be for many dairy farmers, since they sell premium milk to upmarket suppliers and cafés in London, such as Allpress Espresso and Gails. “We’re lucky because our customers are discerning and they generally can afford to choose to use us.”

Even with the additional revenue from the sale of offsets, farmers are likely to need government support to start investing in emissions reduction solutions. More consumers need to start purchasing low-methane products to support the effort, but the products cost more. A 2-litre bottle of Brades milk retails for about £2.70, more than double what supermarkets charge for own-label milk.

“Some people need to buy the cheapest [milk] they can find to feed their families,” says Towers. Supermarkets, he adds, have “a disproportionate amount of power.” They could choose to buy climate-friendly products, rather than engaging in a “race to be the cheapest”.

Nevertheless, he believes that the whole industry can make that shift. “The most important industry around climate change is farming . . . we really are the [one] that has the ability collectively to have a really positive impact, [and] the biggest responsibility, which is feeding everyone else who doesn’t farm.”