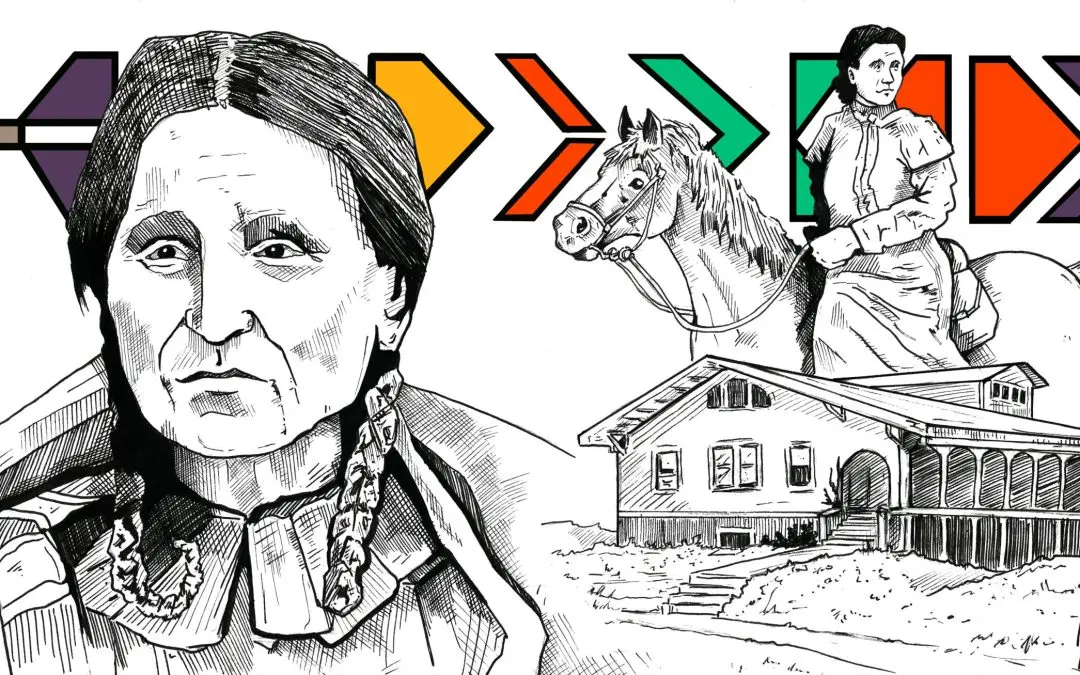

It’s the late 1800s. With no government help in sight, Omaha citizen Dr. Susan LaFlesche is determined to bring health care to her tribe. Decades later, the U.S. still hasn’t gotten around to fulfilling its treaty promise to furnish medicine. So, tribes find a way to take over their health care system, and a quiet social movement is born.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund coverage of Indigenous issues and communities. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Dr. Sue

Imagine the little girl hunched in the candlelight, sitting by the bedside of a sick old woman. She caresses the frail hand and whispers in her ear, promising that help is on the way. The old woman thrashes in agony, but the girl tells her over and over, ”The doctor, he’s coming.”

That little girl, her name is Susan LaFlesche, youngest daughter of the last standing Omaha chief Iron Eye–or, as he prefers, Joseph LaFlesche. It’s 1873 in Omaha territory in Nebraska. The doctor sent word that, yes, he’s on the way, but still he doesn’t arrive. Susan is only eight years old. She doesn’t know the name of the illness, but she knows when someone’s life is ebbing away. She calls for the doctor again.

And again.

Then a fourth time.

The old woman stops thrashing. Her breathing grows fainter. The doctor never comes. And finally, the old woman takes her last breath of life.

“It was only an Indian and it did not matter,” she wrote. “The doctor preferred hunting for prairie chickens rather than visiting poor, suffering humanity.”

Years later, Susan tells this story to explain why she decided to become a doctor. In fact, the very first Native American doctor. Against all odds, she left her family to travel east to attend the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, graduating top of her class in 1889. Then she did something that her professors thought was lunacy. She moved back home to practice medicine.

“It has always been a desire of mine to study medicine ever since I was a small girl, for even then, I saw the need of my people for a good physician.”

A good physician. Right about then, as one century ended and another began, that’s exactly what tribal communities needed most of all. Overlapping waves of epidemics were killing Susan’s people in great numbers: cholera, influenza, dysentery, trachoma, and, worst of all, tuberculosis. She went to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs caring for 1,200 patients living across a 1,300 square mile reservation. That’s the size of a couple of New England states put together. And she made house calls…alone…on horseback.

“My office hours are any and all hours of the day and night.”

Dr. Sue, her patients called her. Native or non-Native, Dr. Sue gave them the medicine they needed.

“I’m not accomplishing miracles, but I’m beginning to see some of the results of better hygiene and health habits. And we’re losing fewer babies and fewer cases to infection.” But reading her letters back to her boss, the BIA commissioner, Francis Leupp, it’s obvious that any progress Dr. Sue was making wasn’t getting a lot of support from the U.S. government. She pleaded with them to give better care to the children in the Indian boarding schools. She told the story of one 18-year-old girl with TB that got shipped home.

“I diagnosed abscess of the lung with no discharge; I sent her to Arizona, but she died in a short while. The Superintendent told me she had been examined in January and passed. Another came home in March; I found her with Tuberculosis of the lung; she lived only six weeks. In spite of all precaution [sic], she infected her mother and grandmother, who both died. There is no telling how many of these infections in that large school could have been prevented by proper examination.”

But her letters fell on deaf ears. Working 20 hours a day, Dr. Sue became sick herself. Still, she kept writing.

“I have broken down from overwork,” she wrote. “I know what a small figure our affairs cut with all the Department has on its hands, but I also know that if you knew the conditions and circumstances to be remedied, you would do all you could to remedy them. The spread of tuberculosis among my people is something terrible. It shows itself in the lungs, kidneys, abdominal track, blood, brain, and glands…Something must be done. The physical degeneration in 20 years among my people is terrible.”

Even her husband died of the disease. Finally, Commissioner Leupp wrote back, “I am sorry to hear that you are now laid aside by illness by active work among your people. They never needed the kind of help, which you give more than they do now.”

But, ultimately, Leupp’s reply?

“Owing to a lack of funds, it is quite impracticable…”

He said maybe some charities could help instead. The federal government just didn’t have enough money for health care in Indian Country.

And as the decades passed, it became a very common refrain.

“Why Do I Even Bother?”

This was the dire health situation of Indigenous communities heading into the 20th Century, rampant disease, and a U.S. government with very little will to fulfill their treaty agreements to provide health care. If any money at all was appropriated, it was usually just to keep Native Americans from spreading disease to soldiers. In fact, Dr. Sue was one of only 77 doctors at the time serving all the tribes in the country. Any money these doctors received was pure luck or through utter willpower like Dr. Sue had. In the end, she got the hospital she wanted built for her people.

“I shall always fight good and hard even if I have to fight alone.”

In 1915, at 49 years old, Dr. Sue died of bone cancer. Not long after that, the country started to recognize the need to provide support to tribes.

President Taft reminded Congress of those long standing promises, “As guardians of the welfare of the Indians,” he told them, “it is our duty to give the race a fair chance for an unmaimed birth, healthy childhood, and a physically efficient maturity.”

And in 1921, Congress passed the Snyder Act for “the benefit, care and assistance . . . and for the relief of distress and the conservation of health . . . for Indians tribes throughout the United States.” It marked the first time that the U.S. made its first direct payments to tribes for health care.

But what I wondered was whether this made a dent in the enormous health needs of tribes at the time. So I reached out to Mark Trahant, the editor of Indian Country Today and a citizen of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe. I got to chat with him on Zoom, his newsroom quiet in the background. A guy with salt and pepper hair and a friendly smile. Behind little round glasses, his eyes reflect someone who thinks fast and deep about whatever he’s working on. He’s done tons of work reporting on the history of Native American health care.

Mark says, sure, now the government was allocating money, but often it didn’t make it to the people who needed it. Like $30-million dollars Congress gave the BIA for tuberculosis. The director at the time decided he needed that money for other things. That kind of corruption discouraged physicians from even seeking aid.

“One of the physicians actually testified to Congress, ‘I don’t know why I even bother coming to Congress because the money never gets there anyway.’”

But finally, in 1955, the BIA created a health program, now known as the Indian Health Service or IHS. It set up clinics and assigned doctors to serve tribal communities. Mark says it didn’t take long for tribes to begin seeing their health improve.

“One of their first actions, I think, was probably most brilliant in that they started to treat issues of health as public health issues,” Mark says. “So they invested heavily in sanitation, for example. And the first few years after IHS was created, the infant mortality rate dropped significantly, to actually, in some places, lower than the general population. And that was because of good access to clean water and sanitation.”

Termination

But one step forward, two steps back because meanwhile, Congress passed a bunch of laws to assimilate Native Americans. Termination laws, they were called. The feds terminated tribal governments and sold off tribal resources and started moving tribes off of reservations to urbanize them. Mark interviewed some of the political movers and shakers who recalled that era on the PBS program Living History. Brad Patterson worked for three presidents: Eisenhower, Nixon, and Ford. He says the termination era left scars.

“[It] destroyed the treaty relationships, protecting their lands, and actually happened to one in more than one Indian tribe. One, in particular, I’m thinking of the Menonomee tribe of Wisconsin, it was given over to private development and sold. The banks took over Indian tribal currency, the finances, and it was a disaster for Indian people.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs picked the Monominee because the Bureau figured the Monominee could survive on the tribe’s lumber industry but that didn’t work out so well. Utah Senator Arthur Watkins says what the government was doing was “freeing the Indian from wardship status” and compared it to freeing slaves after the Civil War. Termination kicked in for the tribe in 1961. The government cut off all the funds they once sent for stuff like roads, schools, utilities, and health clinics. Instantly the tribe started sliding into poverty. This went on for over a decade.

Lots of Native people moved to cities at this time in search of jobs, but things weren’t much better there. By the late 60s, things had gotten so bad, urban Native Americans organized the American Indian Movement. They staged numerous protests, taking over places like Alcatraz Island to spread their message that things needed to change. On their list of demands was “reclaim and affirm the health of Native people.” Around then, Richard Nixon came into office, passionate about the plight of Native Americans because of an Indigenous football coach he’d been close to in high school. He ended up getting behind two major laws that changed things for tribes in America. The first, in 1975, was the Indian Self-Determination Act, which put a stop to termination policies and gave tribes more power to govern themselves. They could even sign contracts with the government to run their own programs, including health clinics. Here’s a quote from Nixon signing a bill to return Blue Lake to the Taos Pueblo Tribe in 1970:

“This bill indicates a new direction in Indian affairs in this country, a new direction in which we’ll have the cooperation of both Democrats and Republicans. One in which there will be more of an attitude of cooperation rather than paternalism. One of self-determination rather than termination. One of mutual respect.”

But the dire need for health care required extra attention. Mark also interviewed Dr. Abe Bergman, a physician working in a Seattle pediatric hospital.

“In the late 60s, it was obvious that some of the most underserved children in the Seattle area were Indian children,” Bergman says. “And I came to know a remarkable leader, Bernie White Bear, who had founded the Seattle Indian clinic. I talked to Bernie and he pointed out, he educated me that the Indian Health Service did not provide any help for urban Indians even though half the Indians in the United States live off of reservations.

Abe had already been working on public health policy with Washington Senator Scoop Jackson, as well as a brand new staffer, Blackfeet citizen Forest Gerard. So Abe took the problem to the two of them.

“I asked Senator Jackson, ‘Do you know that Indians living in urban areas are not covered by the Indian Health Service?’ He said, ‘Yes, I know.’ And I said, ‘Would you be interested in legislation that expanded the Indian Health Service responsibility to urban Indians?’ And he said, ‘Well, that sounds like a good idea.’”

So they all started putting it together. This was called the Indian Health Care Improvement Act and it proposed allocating almost $2 billion for Native American health care. Nixon supported it but was forced to resign before he could sign it. So it got passed on to President Ford.

On September 13, 1976, Ford signed it into law.

Forest Gerard says between the two new Native American laws, the ramifications for tribes were huge.

“What the Nixon Self-Determination Policy did was to say, ‘Indian tribe, you have the right to assume the control and responsibility of programs and services operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and then the Indian Health Service on your reservation.’”

“It’s really a remarkable success story for government in that it intervened, it brought healthcare to a much better level,” Mark says. “Now, when we talk about disparities, we’re talking really about a few years, and it was 10, 20, 30, 40 years at some points. So it has been a real remarkable story.”

And Mark says, unlike the rest of U.S. health care, the Indian Health Service is a real health care system. The main problem with IHS, though, is that–just like in the days when Dr. Sue was trying to fight tuberculosis–there’s never enough money.

A Constant Vigil

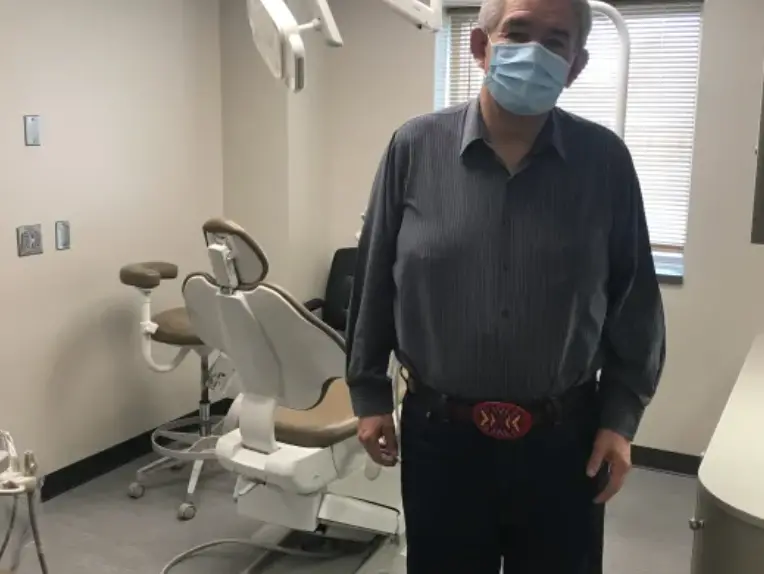

I wanted to hear about that fight from someone I knew who has lived it. Soon after I was vaccinated, I made the long beautiful drive up to the Wind River Reservation in central Wyoming to talk to Richard Brannen. Richard was the CEO of his tribe’s IHS clinic for years. Now he’s nearing retirement age, a little hunched and shuffly, not as tall as he used to be. He told me, as a Northern Arapaho kid, he’d sometimes wait up to five, seven hours to get in to see the IHS doctor because they didn’t “do” appointments. And back then, they gave care using the 72-hour rule.

“We were so severely underfunded that there was a lot of orthopedic procedures we couldn’t do,” he recalls. “And basically, we were subjected to what you call the 72-hour rule, which is loss of life, limb, or eyesight within 72 hours, and then they would pay for the service. But if it wasn’t a possibility of you losing your life or your eyesight or limb or whatever, it would be declared self-pay. And then, typically, the patient is turned over to the collection bureau, and then their credit is ruined.”

And without orthopedic care, people suffered in terrible agony. So to ease their pain, IHS doctors started passing out lots of painkillers instead, leading to addiction.

When Richard grew up, he went to work for IHS running their finances. He didn’t like what he had to deal with there.

“The issue was, in the earlier years possibly the purchasing power was much more. And the issue with IHS and our service funding is, it doesn’t factor in the inflation factor plus growth of populations. So, therefore, per capita expenditures always are decreasing, and they never fully funded it,” Richard says.

On Wind River, he says, the health needs are only funded for 35 percent of the population. Now he was serving as the chairman of the tribe’s business council, too. But a few years ago, something started eating at him.

“One of our greatest enemies is trauma,” he says. “We have historical trauma, intergenerational trauma, we have contemporary trauma. But we don’t even have time to recuperate from that tragedy before another one happens. And so, you know, it’s a constant vigil. Death is your constant companion. You go to funerals when you’re just a little baby. And I still go to funerals.”

But he wondered, why did that trauma start weighing on him now? He told himself his life is good.

“And I tell people a story that, yes, I was comfortable in my job. Basically, I had the systems. I just tweaked it. I knew how to make it operate,” he says. “But God came to my office, stood right by my right side, and he told me enough is enough. And he said, enough early death, enough trauma, enough suffering. And then God took his finger and wrote “enough” on my heart.

And Richard knew what that “enough” meant. It meant he needed to help his tribe take over their own health clinic and start healing their citizens. It wasn’t a task he liked the sound of. He knew other tribes who had done it and it looked hard. But it’d be even harder for the Northern Arapaho because they share their reservation with the Eastern Shoshone. Two sovereign nations living on one piece of soil, a decision the feds imposed on them both way back in the 1800s. It was an uneasy partnership, at the best of times. But once Richard surrendered to doing the thing, he started getting strategic.

“What I did is, I applied for the director of Health and Human Services for the Arapaho Tribe. I worked there [and] we negotiated a 638.”

That number he mentions there — a 638 — it’s the name of a kind of contract that tribes can take out with the feds. Thanks to the Indian Self-Determination Act, when they get a 638, they can take over their health clinic, get the money that would have gone to their federally-managed clinic, but use it the way they see fit.

But getting a 638 ain’t easy…or cheap.

“It took about a year, there were about 17 federal attorneys that were working against us,” Richard remembers. “Because our reservation is unique in Indian Country, two separate sovereigns that have common ownership, it was a very grueling year.”

But today, Richard and I are sitting in a conference room of Wind River Cares, the Northern Arapaho Tribe’s very own clinic. The clinic he dreamed of building. Here it is, bustling with life. After we talk, he gives me a tour.

Hallway after hallway is full of everything a person could need for complete health care and not just physical. There’s also a mental health clinic, optometry, dentistry, physical therapy. In fact, they’re outgrowing this space.

“We purchased the Days Inn hotel,” he tells me. “We’re converting the bottom floor. It’ll be a ten-chair kidney dialysis center. And then the other part will be a diabetic clinic. We want to integrate behavioral health in with that because when a person is diagnosed with diabetes, it’s very traumatic for them. And it’s almost like losing your leg or losing your lifestyle, I guess.”

Walking around Wind River Cares, I think of Dr. Sue and how much she would have loved this place. To offer so much integrated care to her patients in Omaha territory? Just like Richard, it was her dream too. Mark Trahant, the editor of Indian Country Today, says these days about 60 percent of healthcare on reservations is now tribally managed.

60 percent!

That’s what you call a quiet social movement happening in Indian Country.

A Dream Realized by Taylar Stagner

In the hot July sun, bulldozers buzz by, dust is flying everywhere, and the Fort Peck Wellness Center is coming along nicely.

Picture it: I’m in a long dress with the wrong shoes–crocs I believe– in a neon vest and hard hat with all my recording equipment on. I’m a sight to be seen toddling from room to room, trying to look professional as I shuffle passed construction workers. They direct me around the soon-to-be crown jewel of health care on the Fort Peck Reservation in northeast Montana. The $23 million facility started construction the summer of last year and is expected to be finished by this winter.

The facility is large, around 50,000 square feet, and I’m being shown every nook and cranny.

“Hope you like the smell of paint,” Terry Suket, architect and project manager for the wellness center, warns me.

“I love it!” I admit.

“So we’ve entered kind of through the north back door of the building,” he says. “There’s plans for soccer fields, playfields, and stuff out the back. There’s also been some discussion of potentially having a football field out there.”

Terry steers me around, describing what’s what: dental care, therapists, rooms set up for telehealth, workout equipment, a swimming pool, space for elders to socialize, and more space where they can hold events and classes. There’s physical therapy equipment and even a communal kitchen to feed people during large events. You can almost see the community members of Fort Peck a year from now taking advantage of the facilities.

The idea was to make this facility a one-stop-shop for tribal members. I think we’ve all wanted something like this, where you don’t have to travel all the way across town to get a check-up and then to another office to get a prescription. It’s a very forward-thinking building, taking into account what would be best for tribal members. And really what would be ideal for anyone in any community.

The wellness center is also expected to provide 70 full-time jobs when it is complete, and in its construction, has employed many community members as well.

Building A Better Future

One of them is Miles Liley. Miles is Assinibone and he’s a construction worker on the project. He’s been working here for about a year and gives a chuckle when he sees my outfit. Tactically, I use this as my window to ask him questions. He’s carrying power tools, and it’s hot as he wipes sweat from under his hard hat and removes his thick protective glasses. While other construction workers move around us, he tells me about his kids.

“I’d like to bring them here, show them the building. I’m proud of it. I want to show them what I built.”

Miles lost his grandmother and mother to diabetes-related illness and looks forward to when he can come to the wellness center and exercise and get medical treatment in the same building, so the same thing doesn’t happen to him.

“And I don’t want my children to have to suffer or see me suffer through that,” Miles says. “But yes, the building is a big asset to the community.”

He tells me he loves the Fort Peck Reservation, and he’s so excited to be a part of literally building a better future for his community and his kids.

As I walk to my car to return to Billings, about a six-hour drive, the sunset is pink and purple. It starts to rain and I look back at the building as drops start to clean off some of the dust-caked on my forehead. After the long dry summer we’ve had in Montana, the rain is welcome.

The Obituaries

On the drive, I get to wondering how this project all started. When I get back, I track down one of the guys who made it happen. I give him a call and arrange a Zoom meeting.

Kenny Smoker sits on a Zoom call with me from his office on the Fort Peck Reservation in Poplar, Montana. He’s the Director of the Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Program there and a member of the Fort Peck Tribes. Even on the screen, I can see he has discerning eyes and a no-nonsense attitude. He says that making healthcare more accessible to tribal members is essential to improving the quality of life on the reservation. Kenny is all business, but you can tell that’s from years of trying to better the lives of tribal members.

He tells me the project started in 2001 when a group of local high schoolers from Fort Peck constructed a list of things they wanted to see in their town. The list included this wellness center to help close the life expectancy gap between the Indigenous of Fort Peck and their white neighbors.

Fifty-nine years is the average life expectancy for those living on Fort Peck, while for the rest of Montana, it’s seventy-eight. I do some quick math in my head. That’s an 18-year difference.

He says that every two years the tribe does an analysis of death certificates, and the last time Kenny checked, the average age of people dying on the Fort Peck Reservation was dropping. He says he checks every few years, and right now, the average age of death went from 57 to 53.

“On average, if you look at the obituaries on a daily basis–which I do– the numbers are always very low,” Kenny says. “And that’s what we’re trying to make a difference and nothing else. Give people that opportunity to extend life.”

Like many other tribal communities, there is a huge discrepancy in life expectancy between those who live on the reservation and off. When people hear this, they usually ask why? And it’s a lot of reasons at once. Lack of federal funds to tribal clinics. Lack of transportation. Lack of healthcare workers. Lack of treaty rights being made good on.

The reservation has two IHS clinics, mainly for emergency care, but Kenny says the need was much greater than what those clinics could keep up with. He’s interested in helping people thrive, not just survive. He’s been tackling keeping kids off cigarettes and fighting diabetes as well as spearheading the wellness center project.

The federally-run clinics were not making any progress solving Fort Peck’s health crisis. So the tribe started investigating the option of 638-ing.

If they got a 638, it meant they could decide what funding to apply for, what loans to get, and what to do with donations. And they could build their dream wellness center more quickly because there isn’t as much red tape to move through.

Soon Fort Peck even secured other funding sources like new-market tax credits and a grant with the Department of Energy to make the building more energy-efficient.

Kenny says that 638-ing is a part of the rich tapestry of health care fueled by tribal sovereignty.

“We have, like, say medical, mental health and dental services, but we can expand and we can put whatever we feel is important to improve health. We’ve even gotten to the point where we’re addressing the social determinants of health as well,” Kenny tells me.

To 638 or Not To 638

Each tribal community has different needs. One tribal community might want to run just its own pharmacy while another would like to take overall health care needs for its tribal members. And from there it gets more complex. Anyone who has spent time researching Federal Indian Policy knows that it’s opaque and confusing. But, here is what I’ve learned with help from an expert.

In the age of the Zoom interview, Vanessa Tibbets and I talk about what 638 contracts are. She facilitates the transfer of the federal government’s IHS clinics contracts over to locally-run tribal leadership. And she still finds the work dense and intentionally illegible sometimes. She works for the American Indian Public Health Resource Center and she’s also Oglala Lakota. She says that there are pros and cons for tribes considering whether to enter into a 638 contract. A lot goes into the decision to run your own health care clinic. For one, more money goes directly to the tribes instead of to IHS.

“And so when you’re running it yourself, you’re open to more funding avenues,” Vanessa says. “So you’re open to state revenue and privatized health care services and different things like that. And more services are billables. So that tribes are bringing in more money through Medicaid, Medicare, privatized insurance, so that could go toward more health care services being offered.”

Vanessa also says it can be really flexible to the particular situation of a tribe. I remember that Fort Peck wanted to be able to let independent medical contractors use offices in the building. Fort Peck is constructing a whole new building, but a lot of tribes take over the old Indian Health Service buildings once management is switched over to the tribes.

“Some tribes have actually done that completely. And they run their previous IHS clinic or their previous hospitals,” Vanessa says.

But, she says, there is one big reason not to do a 638.

“Some tribes choose not to 638 at all because they believe it is a federal responsibility and a treaty responsibility to provide health care services to tribal people.”

In other words, some tribes want the federal government to make good on its promise to provide healthcare for all the land that was taken from them.

And a lot of times it’s just too expensive to take on all the financial responsibility of running a clinic. There is huge financial risk and building the institutional scaffolding to support a whole clinic takes years. That was the case for Fort Peck. They had to take out loans to help pay for such a large project and not every tribe can do that.

Vanessa also tells me that because a lot of tribes are rural, many services are not readily available. It’s hard to lure medical professionals to hire on when it’s a day’s drive to the nearest metro center. And then, Vanessa says, you take into account the fact that Congress has failed for decades to fully fund IHS.

“And so that makes it really difficult to provide through-services when our hospitals and clinics are only funded at less than 50 percent.”

I’ve even heard that federal prisons are more funded than some IHS clinics.

For all the federal treaty promises to provide health care and for all the land that was taken by force, Indigenous people are dying because of lack of access to good health care. To good medicine.

Vanessa says the decision to 638 a tribal health care program is not made lightly, but many of the tribal programs she’s worked with have benefited from the transition.

The Right To Take Care Of Each Other

When a tribe activates a 638, both Vanessa and Kenny are in agreement that the tribe is exercising a form of tribal sovereignty. Tribal communities know what’s best for them and a 638 contract gives them more freedom to make those decisions.

Fort Peck needed a one-stop-shop for the health and wellbeing of their tribal members, and that’s what they are building. More convenient care that takes into account a whole person. If you need a dentist appointment after your workout? That’s going to be available to you at the Fort Peck Wellness Center. Want to take a dip in the pool after your physical therapy, you got it. It’s all about providing the best, most convenient care.

Tribal sovereignty gives tribal communities control and jurisdiction over their own destiny. We talked in the last episode about how that autonomy has historically been taken away from Indigenous people by failing to supply basic healthcare and how disease was even used as a kind of biological warfare. Reclaiming the right to supply healing and medicine is one way to end that war, once and for all.

Recently, I talked with a Northern Cheyenne Scholar who studies tribal sovereignty, Dr. Leo Killsback. “Yeah, for Indian people, we know what it’s like to be regulated. And we know what it’s like to be questioned at every turn,” Leo says. “For the more successful tribes, in terms of tribes that have been able to get a better handle on their health care and their health services on a reservation, they’re successful because of the commitment of individuals that have fought for what they wanted–whether it’s through litigation, or whether it’s through just demand for what’s what’s rightfully theirs.”

Leo is at Montana State University Bozeman and wrote two award-winning books, A Sacred People and A Sovereign People both about the concept of tribal sovereignty and decolonization, and both are crazy personal stories about his own people, the Northern Cheyenne. Leo says one of the most fundamental ways we can heal from generations of genocide is by reclaiming our right to take care of each other.

“Healthcare has been an issue for Native American people for a long time; we endured smallpox, cholera, and the common cold. And I mean, theoretically, if we could take a look at it from a much larger standpoint, it can be overwhelming. But if you examine it through the lens of even through the lens of a tribal sovereignty perspective, more ground can be covered.”

Leo says that means empowering community members–people like Kenny Smoker with the Fort Peck Wellness Center–who know by heart what issues need to be addressed.

“We see it with diabetes, we see it with other health disparities in Indian Country that Indian nations are committed to protecting their communities, which is something that I think is really important and I think that will continue. I mean, regardless of what our neighbors may think that masks don’t work and what have you, I mean, I think Indian people are committed to protecting ourselves. Last year it was protect our elders; this year, it’s protect our children.”

“Our People Deserve The Best”

I touched base with Kenny Smoker on Fort Peck to see how the Wellness Center is shaping up. He says it’s on schedule to be finished with construction by the end of the year. It’s hard to read his no-nonsense facial expression, but I can tell he’s pleased with how far his tribe has come. Sure, he knows there’s lots more work to be done. A project like this is never truly done.

Kenny says that while 638 contracts have lots of pros and cons, he thinks it was the right decision for Fort Peck. He thinks it’ll help his tribe get ahead of all the health disparities instead of just treating symptoms.

“What this means is, it’s our people deserve the best,” Kenny says. “And we have the resources to give them the best, so we’ll give them the best.”

Kenny says that now is the time to make good on promises made, to better help the people of the Fort Peck reservation and move toward a better future together. I know, I’m getting corny here, but working towards a better future really is driving Fort Peck’s decisions.

“I was on a tribal council years ago, and I went to Congress along with some of our other leaders to say, if we only have this, we can make a change. Well, now we have that ability, we have those resources to make that change.”

There’s lots happening on the Fort Peck Reservation. This fall the tribe took steps to support better infrastructure, to grow the local economy, including overhauling Fort Peck’s web presence. They want to focus on eco-tourism and make their streets safer. The community is moving forward together to build a better future for tomorrow. I truly believe that’s what’s happening. Good news after what seems to be generations of bad news.